Between popular sovereignty and the rule of law

Referenda regarding controversial topics such as the burqa ban are his specialty: Daniel Moeckli, Professor of Public Law with a focus on International and Comparative Law at the University of Zurich, explores the limits of direct democracy with an ERC Grant – and how international standards could be set when dealing with referenda.

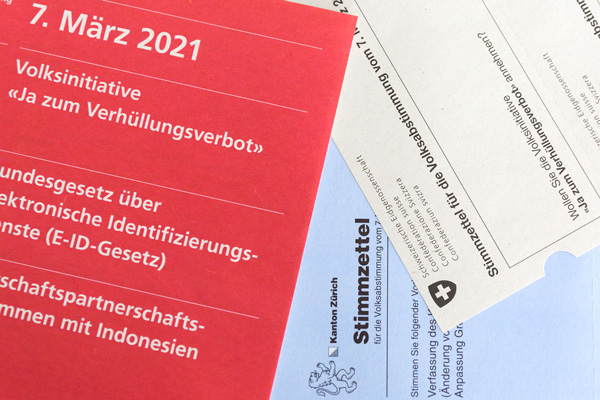

Switzerland voted on the popular initiative «Yes to a ban on full facial coverings» in March. Which law is violated by this ban?

It is debatable whether the ban violates any legal norms. The ban on full facial coverings raises the question whether it is compatible with the freedom of religion and the prohibition of religious discrimination. The European Court of Human Rights has ruled that the bans on face coverings introduced by France and Belgium are compatible with the freedom of religion. However, the UN’s Human Rights Committee decided in the case of the French burqa ban that it violated both the freedom of religion and the prohibition of discrimination.

So, we do not know whether the burqa ban is legal nor not?

Exactly; the ban on full facial coverings is a good example of the problems that may arise when popular initiatives or referenda concerning certain issues are prohibited. It is controversial whether the ban violates human rights. Two bodies arrive at different conclusions. And yet, someone would ultimately have to decide.

You conduct research on the limits of direct democracy based on referenda as the one described above. Was it a specific referendum that encouraged you or rather the overall tendency within Europe towards more referenda?

I have been dealing with this topic for many years – my inaugural lecture in Zurich back in 2013 was dedicated to the popular initiative against the construction of minarets. In Switzerland, we have been dealing with this topic for a long time. In Europe, it is becoming more and more of a problem, which is due on the one hand to the increasing introduction of direct-democratic instruments.

«What has certainly

surprised us

is the diversity of

direct-democratic instruments

among the 47 states.»

Even countries such as the United Kingdom or the Netherlands that had not known referenda before, have started to use them in recent years. On the other hand, as a result of globalisation, more and more states are bound by an increasing amount of international obligations. As a result, the scope of decision-making at the national level is getting narrower. This leads to an increase in conflicts between popular sovereignty and the rule of law.

Since November 2018, you have been working on a pan-European project assessing this tension and trying to resolve the relationship between popular sovereignty and the principle of the rule of law. Are all of the 47 countries belonging to the Council of Europe involved in this project?

Yes. During the first two years we worked on establishing a database we call LIDD Dashboard. Two PhD students have been almost exclusively occupied with this work. You can now find information about all 47 Council of Europe countries in this database: what direct-democratic instruments they have, how the limits are defined and who supervises compliance with these limits. All data was verified by local experts for these 47 states.

How do you find reliable partners in the corresponding countries?

For Eastern European countries, that was sometimes difficult. However, in the end, we did find experts helping us in every country.

There must be an immense accumulation of very different data. How can it be harmonised?

That was possibly the greatest challenge. For example, we have defined seven different categories of direct-democratic instruments. The classification of the data according to these categories cannot be done automatically, but has often required a team decision. In addition, there is the distinction between substantive and formal limits.

What do you mean by this?

Substantive limits preclude certain subject areas from direct-democratic decision-making – for example budgetary or tax matters or national security. Or a national constitution or law may state that anything that violates international law cannot be put to a popular vote. Formal limits concern the freedom to vote, especially the clarity of the referendum question: the voters must be able to understand the subject matter and to decide freely. The requirement of the consistency of the subject matter is also part of this: voters should only have to decide on one single subject and not on two parts that allow for just one answer, as was the case with the Ecopop initiative.

In your project, you incorporate the European Citizen’s Initiative (ECI) that allows EU citizens to call on the European Commission to propose new EU legislation. How important is this initiative?

The ECI is a weak direct-democratic instrument, a so-called agenda initiative, which merely allows citizens to put an issue on the political agenda. Once one million people have signed an initiative, it is handed over to the European Commission which then has to consider it.

«It has become evident

that many countries have

problems in addressing

our research topic – for example,

with defining what a clear

referendum question is.»

Hence, the initiative does not lead to a referendum and the EU cannot be forced to take action. Nevertheless, this instrument is used frequently. Since its introduction in 2012, almost 100 initiatives have been launched, six of which have been successful. For us, the ECI is interesting as it is a supranational direct-democratic instrument.

You look back 30 years. Why did you choose this timeframe?

Because of the Fall of Communism. After 1989, many former communist countries created a new national constitution and introduced direct-democratic instruments. Especially Eastern European states have confronted similar issues with direct democracy as Switzerland, Liechtenstein or Italy since then. For example, there have been popular votes on banning same-sex marriage in Slovenia, Croatia, Romania and Slovakia.

Do you know of many cases in which direct-democratic decisions have violated international or national law?

I cannot yet clearly quantify this. With the database, we have established the basis for a detailed analysis. Now we can go through all of the votes. In a first step we will define the referenda and popular initiatives that are to be classified as debatable. You need a uniform approach to do this. I can only say this much yet: there are quite a few cases in Switzerland, but also in other countries. Hungary held a referendum on EU refugee quotas that quite clearly violated European law. The bans on same-sex marriage in the states mentioned before are problematic, as is the Brexit referendum.

What was the problem with the Brexit referendum?

It is debatable whether a formal limit was violated. The legal consequences of the referendum had not been defined before the vote; it had not been determined in advance what should happen if the «Leave» vote prevailed. The constitutional courts of many European states have held that the clarity requirement means that the legal consequences of the referendum’s outcome must be defined in advance.

For the general public, content-related limits are probably easier to understand than formal ones. Which ones are more important in practice?

Both are important, but formal limits are harder to define. It is difficult to decide whether a referendum question is clear enough or whether it violates the consistency of the subject matter requirement.

The formal limits are more exciting for you?

Yes – because there is more case law we can analyse. There are a number of court decisions on this, in Italy and Portugal for example, but also in Switzerland. These judgments substantiate, for example, the requirements that a clear referendum question must meet. It is difficult to define these requirements in an abstract manner in a law or a constitution. In practice, formal limits therefore pose more problems because they are less specific than, say, substantive limits precluding tax matters or other subject matters.

You are almost half way through your five-year research project. Can you already draw an interim conclusion?

With the database we have established the basis for analysing individual referendums and popular initiatives, checking whether legal limits have been violated and finding out whether there are court decisions on that. What has certainly surprised us is the diversity of direct-democratic instruments among the 47 states.

«Almost more important

than the limits themselves

is the question of

who is in charge

of deciding whether

these limits are met.»

And it has become evident that many countries face problems in dealing with our research topic – for example, with defining what a clear referendum question is. There is a rich jurisprudence addressing such issues, which has not been compared so far and which we will now analyse.

What have been the biggest challenges so far?

Establishing the database involved far more work than anticipated in the beginning, because we had to constantly reconsider and discuss our categorisations and definitions. Last year, the pandemic was a problem. The political scientist in our team works in Cyprus. We specifically looked for team members from various countries. One PhD candidate is from Hungary, as more popular initiatives are launched there than in Switzerland; however, more than 90 percent of them are declared invalid. Before the pandemic, we were able to meet in person on a regular basis and have dinners together, etc. This exchange is missing now.

Now you are looking for minimum standards in dealing with direct-democratic instruments.

Yes, this is the first step. The second step will be to develop recommendations going beyond these minimum standards. Almost more important than the limits themselves is the question of who is in charge of deciding whether these limits are met: is it the parliament, as is the case in Switzerland for federal popular initiatives, a court, or, as is the case in Hungary, an election commission? And how do the procedures look like, that is, for instance, can initiators appeal against these decisions?

Can you already outline these recommendations, the best practices, so to speak?

A minimum standard for substantive limits would be that a popular vote on the death penalty would be impermissible – there seems to be agreement on this across Europe. If you wanted to go beyond that and preclude votes on anything that violates international law or human rights law, you would first have to define what amounts to such a violation. The formal clarity requirement also seems to be a minimum standard across Europe. In terms of institutions and procedures, it seems clear that the body in charge of making these decisions has to have a certain independence. A recommendation going beyond this would be the transparency of the proceedings, for which certain states could be considered examples of best practice.

Will you also make recommendations as to the body that should decide on the permissibility of referenda?

Yes. Especially in Switzerland, the problem with federal popular initiatives is not so much the definition of the limits but the fact that the federal parliament decides on the permissibility of initiatives. There is no possibility of appealing its decision. It is problematic that a political institution may take a final legal decision. Also in other countries it is parliament that decides on popular initiatives, but that it can do so as the final instance is quite exceptional.

Interview with Daniel Moeckli (in German)

Daniel Moeckli

Daniel Moeckli has been Professor of Public Law with a focus on International and Comparative Law at the University of Zurich since 2018. He studied Law at the University of Bern, Switzerland, and qualified as Barrister and Solicitor of the Canton of Bern. After further studies in London, he worked as a Legal Adviser for Amnesty International in London, before obtaining his PhD at the University of Nottingham, UK, and being awarded the Prix Paul Guggenheim for his work. He earned the Diploma in Human Rights Law from the European University Institute (EUI) in Florence, Italy. After three years as a Lecturer in Public International Law and Constitutional Law at the University of Nottingham he joined the University of Zurich in 2009 as Senior Lecturer, was appointed Assistant Professor in 2012 (until 2018) and received his habilitation in 2014. Visiting fellowships and professorships as well as research visits took him to New York, Florence, Jerusalem and Cambridge.

Horizon 2020 Projekt

LIDD: Popular Sovereignty vs. the Rule of Law? Defining the Limits of Direct Democracy

- Programme: ERC Consolidator Grant

- Research team: Daniel Moeckli, Fernando Mendez, Anna Forgács, Henri Ibi, Stephania Karasamani

- Duration: 1 November 2018 – 31 October 2023 (60 months)

- Contribution for University of Zurich: 1’963’935 €