Promoting resilience: the possibilities of individually controlled apps

In a Horizon 2020 project, a multidisciplinary team of 15 researchers in six countries works on mathematically modelling processes contributing to mental health and resilience. The objective is a personalised app with which risk groups can train their stress resilience. The perhaps most exciting role in this project belongs to Psychologist and Professor Birgit Kleim of the University of Zurich.

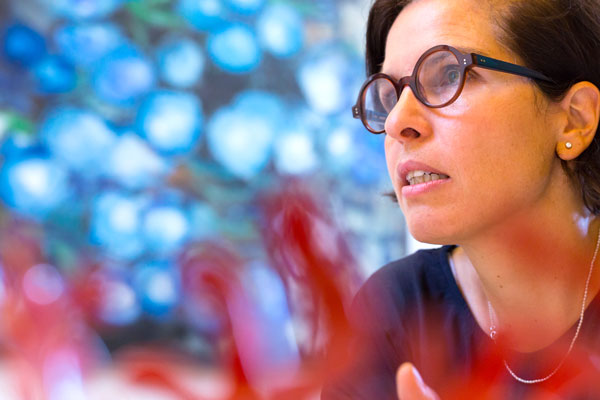

Her work place is located on the top floor of the Psychiatric University Clinic Zurich (PUK), inside a building that is older than 150 years, high above the lake of Zurich. The wooden beams of the roof structure, a semicircular window as well as colourful paintings create a comfortable atmosphere in the room. This is a most welcome contrast to the nearby environment: Birgit Kleim is Professor for Experimental Psychopathology and Psychotherapy and the Head of the Psychological-Psychotherapeutic Service of the clinic that is commonly known as «Burghölzli», named after its location. Here, physicians, psychologists and nursing staff work around the clock with people who suffer from severe mental illnesses.

However, the international research project by the German Birgit Kleim and her team, which has been running for more than three years, is chiefly set in the world of mainly healthy people. The project is called Dynamore, which is an acronym for Dynamic Modelling of Resilience. Usually, more than half of the people are resilient; that is, they are resistant to problems: they are able to cope with life’s adversities and to return to a normal level of functioning after a relatively short time even after traumatic experiences such as a traffic accident, the loss of a loved one or a natural disaster.

«This kind of questions

forces you to deal

with the issue from

another perspective.

This is extremely

rewarding.»

«We are trying to learn from those healthy and resilient people,» Birgit Kleim explains. «We could prevent mental illnesses and possibly severe chronic courses with the help of this knowledge and therewith reduce personal suffering and financial expenses.» Hence, the approach is to focus on health and not on illness. The researchers are not trying to heal an existing illness. They rather aim to help preventing mental problems by means of a personalised app that is always available on one’s smartphone, ready for use.

A project with many facets

The plan is convincing: observing healthy people and their behaviour during burdensome phases of their lives. Among these are the transition to university age or another challenging professional training such as working with the police or in emergency care. Additionally, victims of accidents are monitored already during their recovery process. The psychological, behavioural, neuronal and physiological data are collected and prepared mathematically, i.e., modelled. With these models an app is developed that guides the users in a targeted and individual way and that offers them automatically, if necessary, a so-called intervention, a measure for training and promoting resilience. By this, negative courses and mental illnesses shall be prevented.

In order to attain this objective, researchers from various fields are collaborating. Needed are the expertise of mental health in the area of biology and psychosociology, but also the expertise of mathematics, computer modelling and simulation and health technology.

«Many people do not

seek therapy,

despite their problems.

We can reach some

of these people

by interventions based on

smartphones and the internet

and help them in this way.»

Birgit Kleim is used to thinking beyond the barriers of her own discipline. In another project at the University of Zurich she collaborates with basic researchers, pharmacologists and animal scientists. «We learn a lot from each other and achieve much more than if we were to work in just one discipline,» she states. Other questions are being asked. Mathematicians, for example, want to know how a prototypical patient behaves when experiencing a specific kind of stress. «This kind of questions forces you to deal with the issue from another perspective. This is extremely rewarding,» Kleim says and is convinced: «Such interdisciplinary research is the future of science.»

The demand exceeds the supply

But why are they trying to bring interventions to people with the help of an app? Does this not away with psychotherapists? Kleim negates: «Many people ask this question.» Psychotherapy and prevention measures have two problems, she explains. «In the end, psychotherapy only reaches a part of the people who need therapy. Many people do not seek therapy, despite their problems. We can reach some of these people by interventions based on smartphones and the internet and help them in this way.»

The second problem is the extent of therapeutical demand. The waiting lists for therapy are very long. Thus, many patients receive treatment many years after the initial outbreak of their disease when it has already become chronic and the persons are already facing social problems; they may have already lost their job or partner and additional symptoms have emerged. This kind of problems might be prevented at an early stage with the app. And: in therapy, the aim is to combine psychotherapy with the app’s support between the individual counselling sessions. Therefore, the app is not a competition but a welcome expansion in psychotherapy.

Scientific work is creative

The project now stands at half-time – and can already present concrete results. Kleim explains: «It took almost an entire year to prepare the study. During that time, we had already discussed many preliminary considerations – and were able to refer to a preceding study.» The colleagues in Mainz and Freiburg extracted mathematical data from this study and processed them into factors showing what constitutes resilience. They delivered these factors to Birgit Kleim’s team whose task then was to change these factors specifically by means of an intervention and to create the intervention beforehand.

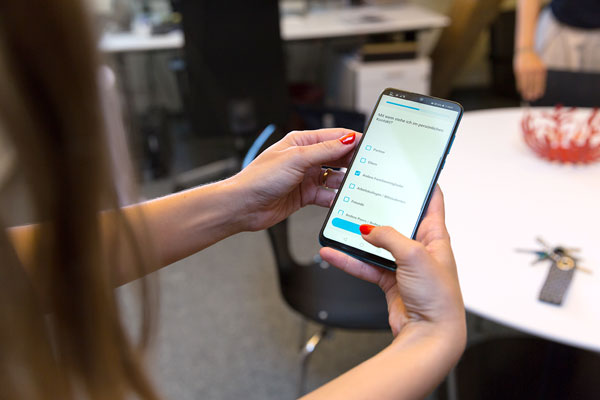

The first factor was the so-called «positive reappraisal», the positive revaluation of an experience. The second factor was the «reward sensitivity». Herewith, the doctoral candidate Marta Marciniak now creates two different apps that are tested continuously by test persons – manly students from Zurich, but also from abroad such as Poland. Their feedback is directly applied to the further development of the final app.

The young woman from Poland is responsible for both the content and the design of the app. Her enthusiasm is tangible when she tells us about her work and shows us the current version of the app on her smartphone. «Developing the app is so much fun,» she says. The work is highly creative because it lets her devise various versions in a playful way. The best part of her work, however, is when she sees that the app truly helps people to effectively reduce their stress level.

«This is one of the most

important questions

of the project and

we promised to deliver

the answer.»

How much of their personal lives are the test persons willing to reveal? «We begin with simple questions such as ‘how happy are you?’ etc.,» Marta Marciniak states. «But we also ask about physical activities, the social environment, the main challenges and there are also some very personal questions.» However, she is convinced that the interviewees like to share their lives with her because they know that everything remains anonymous. Not even Marciniak knows who gave the respective answers.

The two scientists and their European colleagues of the Dynamore Project then further develop the intervention step by step based on the answers given by the test persons. The researchers call these mechanistic therapy tools via mobile phone Ecological Momentary Intervention (EMI). Ecological stands for everyday life versus practice atmosphere: the measures are offered in real life and not in a therapeutical setting.

The algorithm decides

But how do you decide who needs help and at which point the app offers an EMI, respectively? «This is one of the most important questions of the project and we promised to deliver the answer,» Birgit Kleim explains. «Based on the model we aim to develop a decision algorithm that says: now this person is stressed beyond a certain limit value. And then the intervention is triggered and offered.» The user has the option to postpone the intervention by pressing a button in case the offer arrives at an inconvenient time, for example during an exam.

The final product is to be used commercially. Potential customers are not only police forces for their future police officers during the first year of training. Universities, too, can offer this app to their students, retirement homes to their nursing staff and emergency units to their nursing specialists. In addition, commercial enterprises might be interested in offering this tool to their employees to promote resilience in the working world and prevent potential absences from work.

It is already certain: the continuous pandemic has taught us all about resilience and its importance in times like these. Hence, smartphone-based interventions with which many people can train their resilience are unquestionably of great value.

Interview with Birgit Kleim (in german)

Birgit Kleim

Birgit Kleim has been Professor for Experimental Psychopathology and Psychotherapy at the University of Zurich and President of the German-speaking Society for Psychotraumatology (DeGPT) since 2016. She was born in Marburg, Germany, in 1975 and studied at the German University of Freiburg. She then completed her PhD about post-traumatic stress disorder at King's College in London, UK. There, and also at Maudsley Hospital, she thereafter worked for three years as a Research Fellow at the Institute of Psychiatry. In 2009, she joined the University of Basel as a Senior Researcher. Since 2010, she has been working at the Department of Psychology of the University of Zurich. Birgit Kleim is married and the mother of two children.

Horizon 2020 project

DynaMORE: Dynamic modelling of resilience

- Programme: Kollaboratives Projekt (12 Partner)

- Duration: 1. september 2019 – 31. august 2023 (48 months)

- Contribution for University of Zurich: 562’553 €